Enhancing Kubernetes Security with User Namespaces

Content

Enhancing Kubernetes Security with User Namespaces

🛡️ Introduction

User namespaces in Kubernetes offer a robust mechanism for enhancing security and flexibility. This blog post explores the benefits of user namespaces, their implementation, and how they contribute to a more secure Kubernetes environment.

User namespaces in Kubernetes provide several ways to improve workload security, although they can, under certain uncommon configurations, increase the attack surface of clusters. By remapping UIDs and reducing privileges, user namespaces enhance isolation for applicable workloads.

📚 Background

User namespaces are not a new concept. The Linux kernel manual mentions user namespaces starting with v3.8. Since then, user namespaces have been a core technology behind rootless containers. Given that current kernel versions are in the 5.x range, user namespaces have had ample opportunity to evolve. However, their complexity and potential security implications must be recognized: their use opens previously untested code paths. Despite being readily available in the kernel, several Linux distributions chose to disable user namespaces by default to allow the feature to mature. Kubernetes developers adopted a similar approach.

🗂️ Kubernetes Versions and User Namespaces

- Kubernetes v1.25: Introduced alpha support for Linux user namespaces (userns). This feature is touted as an additional isolation layer that improves host security and prevents many known container escape scenarios.

- Kubernetes v1.28: Lifted the restriction on user namespaces for stateless pods.

- Kubernetes v1.30: Moved user namespaces to beta, enabling broader usage and introducing custom ranges for UIDs/GIDs mapping.

🎯 Motivation

From user_namespaces(7):

User namespaces isolate security-related identifiers and attributes, in particular, user IDs and group IDs, the root directory, keys, and capabilities. A process's user and group IDs can be different inside and outside a user namespace. In particular, a process can have a normal unprivileged user ID outside a user namespace while at the same time having a user ID of 0 inside the namespace; in other words, the process has full privileges for operations inside the user namespace, but is unprivileged for operations outside the namespace.

The goal of supporting user namespaces in Kubernetes is to run processes in pods with different user and group IDs than in the host. Specifically, a privileged process in the pod runs as an unprivileged process in the host. If such a process breaks out of the container to the host, it will have limited impact as it will be running as an unprivileged user there.

🔒 How User Namespaces Improve Workload Security

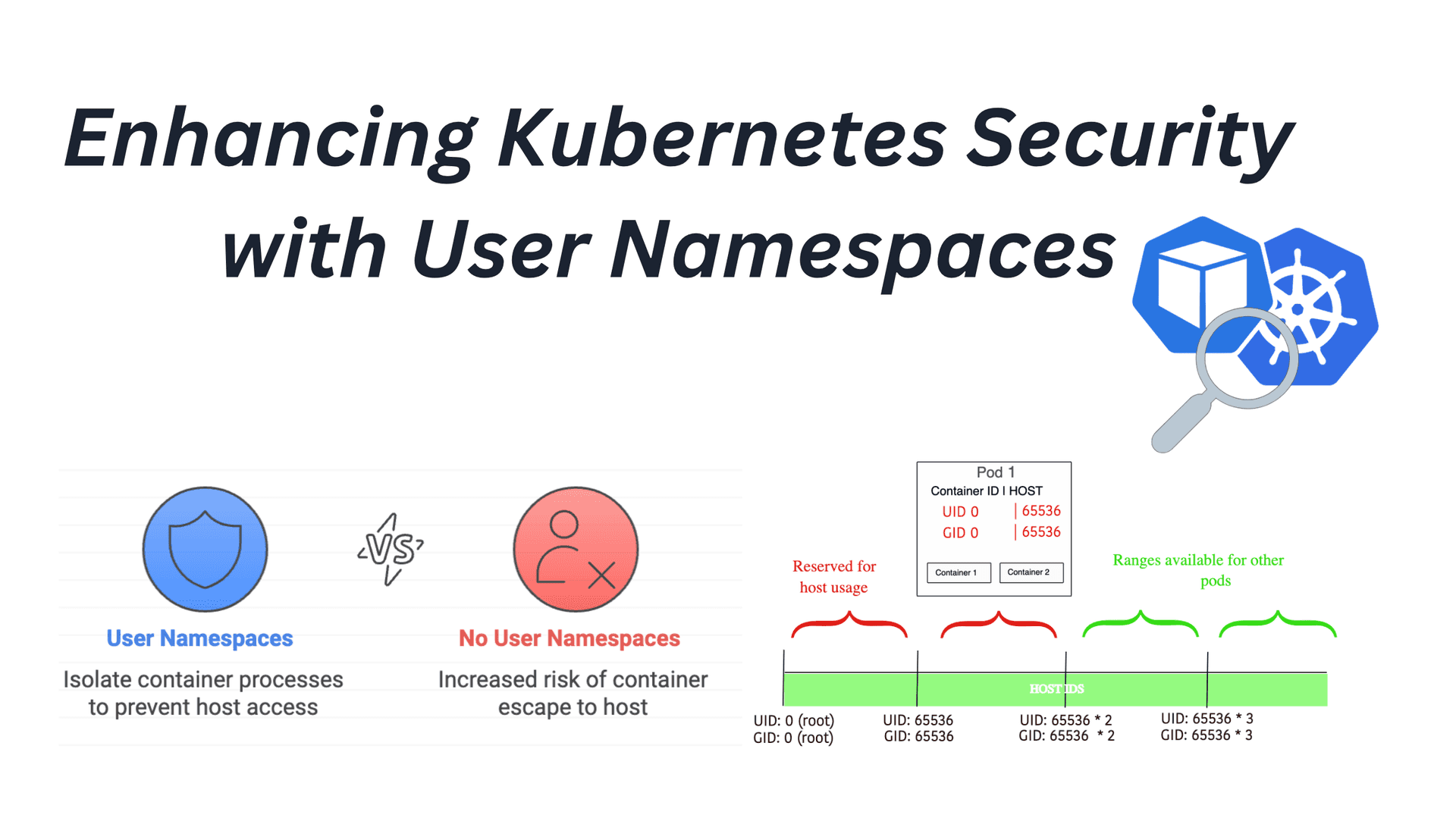

Mitigating the Impact of Container Escape

The main motivation behind user namespaces in the container context is curbing the potential impact of container escape. When a container-bound process running as root escapes to the host, it is still considered a privileged process with its user ID (UID) equal to 0. However, user namespaces introduce a consistent mapping between host-level user IDs and container-level user IDs that ensures a UID 0 on the container corresponds to a non-zero UID on the host. To eliminate the possibility of UID overlap with the host, every pod receives 64K user IDs for private use.

User Namespace Mapping Between Host and Container User IDs

As a result, even if a process is root (i.e., UID 0) inside the container, escaping to the host will only entitle it to access resources associated with UID X.

Moreover, an escaped process with a user namespace would be blocked from accessing resources such as:

- Changing the system time (CAP_SYS_TIME)

- Loading a kernel module (CAP_SYS_MODULE)

- Creating a device (CAP_MKNOD)

/etcconfig files- Devices in

/dev - The

/home/rootdirectory storing potential secrets - Kubelet config, which is commonly used for lateral movement within the cluster and is only readable by the root process on the cluster host

- Unix sockets with root ownership

- TCP/UDP sockets with root ownership

🌟 Benefits

- Enhanced Security: User namespaces isolate security-related identifiers and attributes, reducing the risk of privilege escalation attacks.

- Flexibility: Allows running processes in pods with different user and group IDs than in the host, providing more control over permissions.

- Mitigation of Vulnerabilities: Helps mitigate several known vulnerabilities, such as CVE-2019-5736 and CVE-2021-25741.

A process running as root in a container can run as a different (non-root) user in the host; in other words, the process has full privileges for operations inside the user namespace, but is unprivileged for operations outside the namespace.

You can use this feature to reduce the damage a compromised container can do to the host or other pods in the same node. There are several security vulnerabilities rated either HIGH or CRITICAL that were not exploitable when user namespaces are active. It is expected user namespaces will mitigate some future vulnerabilities too.

Without using a user namespace, a container running as root, in the case of a container breakout, has root privileges on the node. And if some capability were granted to the container, the capabilities are valid on the host too. None of this is true when user namespaces are used.

A user namespace is a Linux feature that isolates the user and group identifiers (UIDs and GIDs) of the containers from the ones on the host. The identifiers in the container can be mapped to identifiers on the host in a way where the host UID/GIDs used for different containers never overlap. Furthermore, the identifiers can be mapped to unprivileged non-overlapping UIDs and GIDs on the host. This brings two key benefits:

-

Prevention of Lateral Movement: As the UIDs and GIDs for different containers are mapped to different UIDs and GIDs on the host, containers have a harder time attacking each other even if they escape the container boundaries. For example, if container A is running with different UIDs and GIDs on the host than container B, the operations it can do on container B's files and processes are limited: only read/write what a file allows to others, as it will never have permission owner or group permission (the UIDs/GIDs on the host are guaranteed to be different for different containers).

-

Increased Host Isolation: As the UIDs and GIDs are mapped to unprivileged users on the host, if a container escapes the container boundaries, even if it is running as root inside the container, it has no privileges on the host. This greatly protects what host files it can read/write, which processes it can send signals to, etc. Furthermore, capabilities granted are only valid inside the user namespace and not on the host, which also limits the impact a container escape can have.

Without using a user namespace, a container running as root in the case of a container breakout, has root privileges on the node. And if some capabilities were granted to the container, the capabilities are valid on the host too. None of this is true when using user namespaces.

There are many known CVEs (and likely many more as-yet unidentified vulnerabilities) that are partially or completely mitigated by the use of user namespaces.

Implementation

Pod.spec Changes

The following changes will be done to the pod.spec:

pod.spec.hostUsers:*bool. - If true or not present, uses the host user namespace (as today). - If false, a new user namespace is created for the pod. - By default, it is not set, which implies using the host user namespace.

Support for Pods

Make pods work with user namespaces. This is activated via the bool pod.spec.hostUsers.

The mapping length will be 65536, mapping the range 0-65535 to the pod. This wide range makes sure most workloads will work fine. Additionally, we don't need to worry about fragmentation of IDs, as all pods will use the same length.

The Kubernetes implementation was redesigned in 1.27, so the requirements are different for versions pre and post Kubernetes 1.27.

Please note that if you try to use user namespaces with containerd 1.6 or older, the hostUsers:

false setting in your pod.spec will be silently ignored.

Kubernetes 1.25 and 1.26

- Containerd 1.7

- You can use runc or crun as the OCI runtime:

- runc 1.1 or greater

- crun 1.4.3 or greater

You can also use containerd 2.0 or above, but the same requirements as Kubernetes 1.27 and greater apply, except for the Linux kernel. Bear in mind that all the requirements there apply, including file-systems supporting idmap mounts. You can use Linux versions:

- Linux 5.15: you will suffer from the containerd 1.7 storage and latency limitations, as it doesn't support idmap mounts for overlayfs.

- Linux 5.19 or greater (recommended): it doesn't suffer from any of the containerd 1.7 limitations, as overlayfs started supporting idmap mounts on this kernel version.

Kubernetes 1.27 and greater

- Linux 6.3 or greater

- Containerd 2.0 or greater

- You can use runc or crun as the OCI runtime:

- runc 1.2 or greater

- crun 1.9 or greater

Furthermore, all the file-systems used by the volumes in the pod need kernel-support for idmap

mounts. Some popular file-systems that support idmap mounts in Linux 6.3 are: btrfs, ext4, xfs,

fat, tmpfs, overlayfs.

The kubelet is in charge of populating some files to the containers (like configmap, secrets, etc.). The file-system used in that path needs to support idmap mounts too. See the Kubernetes documentation for more info on that.

Stripping Unnecessary Privileges

Privileged containers running in their own user namespace are isolated and therefore their capabilities cannot harm the host. For example, Kubernetes lacks support for FUSE filesystem mounting. One workaround is adding a spec to mount a GCP bucket at a postStart event with the required CAP_SYS_ADMIN permissions for the initial namespace.

spec:

containers:

- name: my-container

securityContext:

privileged: true

capabilities:

add:

- SYS_ADMIN

lifecycle:

postStart:

exec:

command: ["gcsfuse", "-o", "nonempty", "your-bucket-name", "/etc/letsencrypt"]However, SYS_ADMIN is a powerful capability. In this case, implementing a user namespace would eliminate the need to specify privileged: true and grant SYS_ADMIN, drastically reducing the host’s attack surface.

Demo

Run a Pod that uses a User Namespace

A user namespace for a pod is enabled by setting the hostUsers field of .spec to false. For example:

apiVersion: v1

kind: Pod

metadata:

name: userns

spec:

hostUsers: false

containers:

- name: shell

command: ["sleep", "infinity"]

image: debianAttach to the container and run readlink /proc/self/ns/user:

kubectl attach -it userns bashRun this command:

readlink /proc/self/ns/userThe output is similar to:

user:[4026531837]Also, run:

cat /proc/self/uid_mapThe output is similar to:

0 833617920 65536Then, open a shell in the host and run the same commands.

The readlink command shows the user namespace the process is running in. It should be different when it is run on the host and inside the container.

The last number of the uid_map file inside the container must be 65536, on the host it must be a bigger number.

If you are running the kubelet inside a user namespace, you need to compare the output from running the command in the pod to the output of running in the host:

readlink /proc/$pid/ns/userreplacing $pid with the kubelet PID.

🏁 Conclusion

User namespaces in Kubernetes provide a robust mechanism for enhancing security and flexibility. By isolating security-related identifiers and attributes, they reduce the risk of privilege escalation attacks and provide more control over permissions. Implementing user namespaces involves changes to the pod specification and container runtime interface, but the benefits in terms of security and flexibility make it a worthwhile endeavor.